![]() Burial

Customs in Norman England

Burial

Customs in Norman England

![]()

By

the 11th - 12th centuries the church was firmly of the view that the souls

of the dead would be judged by God at the Last Judgement, a theme popular

in the art of the period. While the souls of the wicked went to hell, those

of the good went to heaven provided they had had a proper burial in holy ground.

By

the 11th - 12th centuries the church was firmly of the view that the souls

of the dead would be judged by God at the Last Judgement, a theme popular

in the art of the period. While the souls of the wicked went to hell, those

of the good went to heaven provided they had had a proper burial in holy ground.

The right to burial was jealously guarded by churches as a source of income, and so space in graveyards was intensively used, especially in towns, and earlier burials were regularly disturbed by later ones. Typically, 11th - 12th century graves were shallow bath-shaped pits just large enough to contain the body of the deceased. They were aligned east-west or adopted the alignment of the associated church.

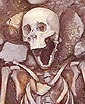

The

body itself was usually laid on its back with legs extended and arms down

by the sides or crossed over the chest, abdomen or pelvis. A common custom

in the 11th- 12th centuries was the placing of stones by the skull of the

deceased to keep it upright perhaps so that he or she would be sure to see

Christ on the Day of Judgement. It is likely that many of the dead were simply

buried in a winding sheet, but wooden coffins were often used and a wealthy

person would sometimes be given a stone sarcophagus.

The

body itself was usually laid on its back with legs extended and arms down

by the sides or crossed over the chest, abdomen or pelvis. A common custom

in the 11th- 12th centuries was the placing of stones by the skull of the

deceased to keep it upright perhaps so that he or she would be sure to see

Christ on the Day of Judgement. It is likely that many of the dead were simply

buried in a winding sheet, but wooden coffins were often used and a wealthy

person would sometimes be given a stone sarcophagus.

The

place in which people were buried was closely related to their wealth and

social status. The majority ended up in their local churchyard, but others,

if able to pay, chose monastic houses because they felt the monks were more

dedicated to the service of God than their parish priests. Burial was allowed

inside churches for certain people of high status, principally kings, princes

and senior churchmen.

The

place in which people were buried was closely related to their wealth and

social status. The majority ended up in their local churchyard, but others,

if able to pay, chose monastic houses because they felt the monks were more

dedicated to the service of God than their parish priests. Burial was allowed

inside churches for certain people of high status, principally kings, princes

and senior churchmen.